Congress: How We Got Stuck

Part 2 of 3. How the vast majority of races for the U.S. House became uncompetitive through gerrymandering, a supine Supreme Court, geographic sorting, and the politics of safe seats.

Hello from Cape Town, where I’m with my wife, Danet, who’s attending a conference. It’s an intriguing place to write about democracy: South Africa established its own just three decades ago under Nelson Mandela’s extraordinary leadership — and this young democracy now faces the challenges of growing up.

For now, we return to Part Two of our deep dive into the stunning lack of competition in U.S. House races — the heart of American democracy. Last week we explored the problem (which you can read here). Next week, solutions. Today, the forces that brought us here.

What we’ll learn:

Technology has transformed gerrymandering from political art to mathematical science — allowing parties to preordain outcomes.

The Supreme Court’s retreat in Rucho v. Common Cause has stripped away federal oversight, leaving state partisans free to entrench power.

Together with geographic sorting, closed primaries, and the dominance of money, these forces have created a self-perpetuating system where competition — the lifeblood of democracy — has all but disappeared.

Solving For tackles one pressing problem at a time: what’s broken, what’s driving it, and what can be done. New posts weekly. Learn more.

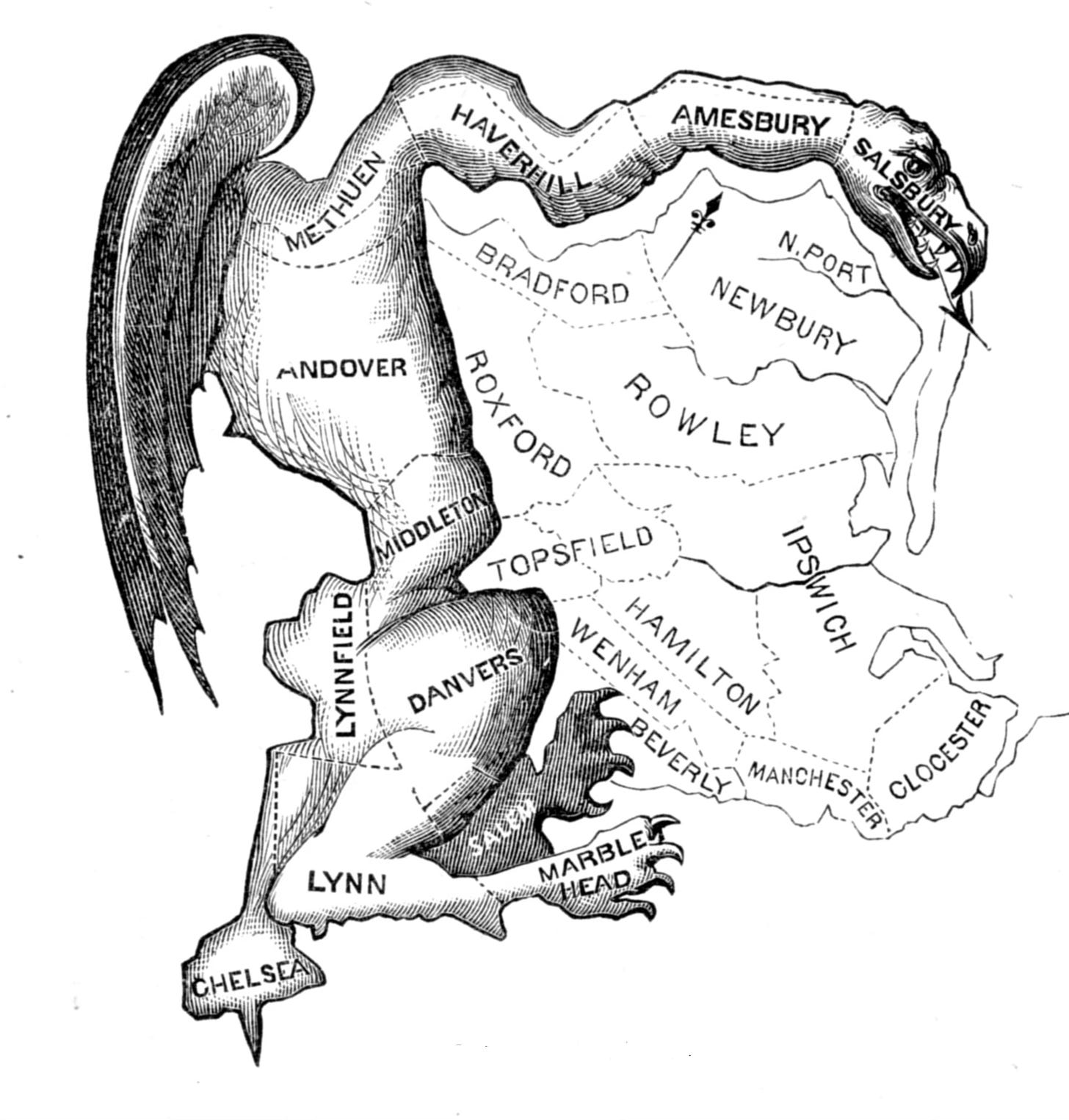

In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts faced a defining choice. His party, the Democratic-Republicans, had pushed through a redistricting plan designed to lock in their control of the state legislature. The map twisted across counties in strange, contorted shapes—so odd that one district snaked around towns in Essex County like a salamander.

Gerry, a cautious man and veteran of the Revolution, disliked the scheme but signed it anyway. Soon after, a Boston newspaper published a cartoon of the district as a fantastical beast with claws, wings, and a dragon’s tail. The caption: “The Gerry-mander.”

The name stuck — though not for the reasons Gerry might have hoped. A signer of the Declaration of Independence and lifelong skeptic of concentrated power, he was among the few delegates who refused to sign the U.S. Constitution at the Constitutional Convention, fearing it lacked safeguards against tyranny. Yet his name would become shorthand for one of democracy’s most enduring distortions: drawing political lines to protect the powerful and silence the public.

Put another way: politicians choosing their voters, rather than voters choosing their politicians.

More than two centuries later, the gerrymander has evolved from hand-drawn maps on parchment to algorithmic precision — data-driven software capable of all but predetermining election outcomes. This year it’s being deployed on a scale unseen in modern memory, with consequences we’re only beginning to grasp.

It’s a central gear in the machinery that has quietly drained competition from American democracy — leaving fewer than one in ten races for the U.S. House competitive. In 2024, only 8 percent of congressional races were decided by fewer than five points, according to an analysis by The New York Times. The result: a politics of safe seats and hardened sides, where polarization deepens and Congress drifts further from problem-solving.

For Part Two in our series — The Democracy Deficit: Solving for Competition in the People’s House — we examine how the system locked itself in: through technology that turned gerrymandering from art to science, a Supreme Court that stood aside, demographic sorting that clustered like-minded voters, primaries and media that reward purity, and campaign finance that punishes independence.

Together, these forces have created a self-reinforcing cycle that has turned the House — once the “People’s House” — into something closer to a fortress, with the very people it was built to represent standing outside its walls.

The Precision of Power

Gerrymandering is not new. What’s new is the ability to do it with mathematical precision.

Modern mapmakers wield geographic information systems software, micro-targeted voter files, and algorithms that can forecast partisan outcomes down to the city block. What once took weeks now happens in hours — judgment replaced by statistical models, intuition by math. The result is a revolution in control, where district maps are drawn not to represent voters but to engineer results.

Both parties use these tools, but the imbalance in some states is staggering.

Take Wisconsin’s 2018 State Assembly elections. Though not for Congress, they offer a vivid example of how modern gerrymandering undermines democracy. That year, Democrats won 54 percent of the statewide vote but captured only 36 percent of the seats. Post-election analyses found that the Republican-controlled legislature, using sophisticated mapping software, had drawn districts that packed Democratic voters into a handful of urban strongholds while spreading Republican voters thinly but efficiently across the rest — enough to win comfortably almost everywhere else.

The result: a commanding Republican majority built on a minority of votes.

It was, according to University of Wisconsin political scientist Barry Burden who also leads the Elections Research Center in Madison, “a beautiful gerrymander.”

Similar asymmetries appeared in North Carolina, Texas, and Illinois—each a reminder that technology built to illuminate democracy can also be weaponized to contain it. The power to draw lines, now exercised with algorithmic accuracy, has become the power to choose voters. In many states, elections are decided before ballots are cast — representation less a matter of competition than of code.

Now an all-out gerrymandering war has erupted to tilt next year’s mid-term elections. It was kicked off by President Trump who — facing a tough fight to keep control of the House — cast aside the traditional ten-year redistricting cycle and demanded that Texas redraw its map immediately — and do so to favor Republicans.

“We are entitled to five more seats,” Trump said of Texas Republicans, which promptly redrew its map, netting five additional Republican-leaning congressional districts.

This week California voters sought to neutralize Texas’ move by approving its own gerrymandered map that nets five Democrat-leaning seats. But it hasn’t stopped there: North Carolina, Ohio and Missouri have also redrawn boundaries; a host of other states are considering it.

“The wheels are coming off the car right now,” said Nathaniel Persily, a professor at Stanford Law School who has studied gerrymandering. “There’s a sense in which the system is rapidly spiraling downward, and there’s no end in sight.”

The Supreme Court Stands Down

Even as technology gave politicians unprecedented power to shape the electorate, the institution meant to guard against such excesses stepped back — leaving democracy’s lines to be drawn by those who stand to benefit most.

The Supreme Court’s 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause cemented this new reality — and we’re still learning the impacts of that decision. In a 5–4 ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that partisan gerrymandering, however “incompatible with democratic principles,” was a “political question” that does not violate the constitution and is beyond the reach of federal courts.

Roberts conceded that “excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust,” but concluded it “does not mean that the solutions lie with the federal judiciary.”

Remarkably, the Supreme Court declared itself powerless.

Justice Elena Kagan responded with a blistering dissent, which she read from the bench to underscore her alarm. Gerrymandering, she warned, “imperils our system of government,” and that the Court had abdicated its duty to defend democracy’s foundations. “None is more important than free and fair elections,” she continued.

“Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law,” she added, “this was not the one.”

The message was unmistakable: federal courts would no longer police the fairness of congressional maps. Power shifted back to the states—where partisan legislatures could now draw with fewer constraints.

The effects were swift. In North Carolina, for instance, its 14-member U.S. House delegation — evenly split at seven Republicans and seven Democrats — became a ten to four Republican advantage in 2024 after the state Supreme Court flipped partisan control.

Now, Louisiana v. Callais, a case currently pending at the U.S. Supreme Court, threatens to erase the last federal guardrail: Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The case stems from Louisiana’s lone Black-majority district among six seats, despite the state’s population being one-third Black. Courts ordered a second Black-majority district, but opponents sued that the fix itself was unconstitutional. If the justices strike down Section 2, courts could be barred from requiring even racially representative districts — ending the last meaningful federal check on gerrymandering.

As The New York Times’ Nate Cohn and Jonah Smith wrote this month, striking down Section 2 would mean there “would be no meaningful law that might deter a 38–0 Texas congressional map that unanimously elected Republicans, or a 52–0 map in California with nothing but Democrats.”

What this all means: The pursuit of fair and representative elections has given way to raw power and political advantage — with no federal court left to intervene.

The Great American Sort

In 2008, journalist Bill Bishop published The Big Sort, arguing that Americans were increasingly clustering by choice — seeking out neighborhoods, schools, and communities filled with people who think, vote, and worship like they do. What began as lifestyle preference has evolved into a defining feature of modern American politics. The result is a self-reinforcing geography of identity: our ZIP codes now predict our politics more reliably than our income or education.

Over the past few decades, this divide has hardened into a stark urban–rural split. Cities have grown deep blue, rural areas deep red, and the suburbs between them have become the decisive battlegrounds of American elections. Drive an hour in almost any direction from a major metropolitan center, and the political landscape shifts as sharply as the scenery — from Democratic city blocks to Republican small towns.

That sorting doesn’t just happen on the map; it happens in daily life. Cable news, social media feeds, and local culture now amplify the sameness around us. We read, watch, and share within ideological bubbles. We go to churches, gyms, and schools where political diversity is increasingly rare. Cross-cutting conversations — the kind that once took place over backyard fences or local PTA meetings — have grown scarce.

The consequences for democracy are profound. Even without gerrymandering, many congressional districts would tilt strongly to one side simply because of where Americans choose to live. Partisan map-drawing may sharpen the edges, but the underlying terrain itself has already polarized. Representation, once a contest of ideas, now mirrors geography more than persuasion.

A map of the United States today tells the story in color: blue urban cores, red rural expanses, and ever-thinner bands of purple fading between them — a visual portrait of a nation increasingly sorted by choice, and divided by design.

Protecting the Duopoly

If geography and mapmaking have carved America into red and blue zones, the way we run our elections has deepened the divide.

As we discussed in Part 1 of this series, in most House districts, the general election is little more than a formality; the real contest takes place months earlier, in a low-turnout primary dominated by the most committed partisan voters. The result is predictable: candidates learn that survival depends not on appealing to the broad middle, but on energizing their base.

That problem is magnified by the nearly two dozen states with closed primaries that exclude millions of independent voters from participating at all — further pushing candidates to the edges. Yet despite widespread frustration, both parties have fought to preserve a system that puts a premium on party control.

Florida offers a case in point. In 2020, voters considered a constitutional amendment to open primaries to all voters. The proposal — led by Miami businessman Mike Fernandez and attorney Gene Stearns — drew an unusual coalition of opponents: Democrats and Republicans joined forces to defeat it.

Joe Gruters, then Chairman of the Republican Party of Florida, marveled: “How rare do you have the Republican Party of Florida, Democratic Party of Florida, the ACLU, and the League of Women Voters and then the Black Caucus” all aligned in opposition.

But Glenn Burhans, chairman of All Voters Vote, which worked to pass the amendment, countered “it’s really about determining the true will of the people, and when I say, ‘the people,’ all registered voters in Florida, and not just leaving it to the small sliver of the ideological wing of either major party.”

In the end, 57% of Florida voters agreed with Burhans. They wanted the right to vote directly for their candidate of choice. Yet, it wasn’t enough: Florida law requires 60% for a constitutional amendment to pass.

The status quo prevailed. The duopoly endured.

Money Seals the Deal

Each of the prior forces explains how competition erodes:

Gerrymandering predetermines outcomes.

The Supreme Court removes federal oversight.

Geographic sorting hardens the map.

Closed primaries filter out moderates.

But money is what cements the system — keeping incumbents safe, punishing dissenters, and deterring challengers. It ensures that the structural barriers aren’t just theoretical, but permanent.

Once elected, members of Congress almost never lose. Nearly 95 percent win reelection, protected by safe seats, name recognition, and the steady flow of money to those already in power. Lobbyists and PACs invest where influence is secure, not where it might shift. Challengers face a credibility gap so wide that many never even try.

Inside Congress, money enforces discipline. PACs and outside groups reward ideological loyalty and punish independence, signaling that crossing party lines can invite a well-funded primary challenge. The same forces that make incumbents safe from the other party make them vulnerable to their own.

In theory, incumbency should give members freedom. In practice, safe seats breed rigidity, rigidity attracts polarized donors, and polarized donors make those seats even safer.

Democracy depends on uncertainty — the possibility of losing. Yet, increasingly, that’s the one thing today’s system no longer allows.

Finding our way back

The story that began with a salamander-shaped district in Massachusetts now stretches across the entire map of the United States — only this time the creature is digital, data-driven, and nearly impossible to catch.

Two centuries later, the problem Elbridge Gerry set in motion has metastasized into something far larger: a system where maps, money, and machinery conspire to protect power from competition.

The question is no longer how we got here — that story we can trace. The question is how we find our way back to a democracy where voters choose their representatives, not the other way around.

Gerry himself eventually came around. After the Bill of Rights was adopted, he embraced the Constitution he once refused to sign, believing its new safeguards could restrain power and protect the people.

The question before us now is whether we can do the same — and restore the safeguards our democracy has lost.

Next week: Solutions — ways to bring competition back to the “People’s House.”

Note: Prefer to listen? Use the Article Voiceover at the top of the page, or find all narrated editions in the Listen tab at solvingfor.io.

Previous and Current Deep Dives

The 21st Century’s Oil: Solving For China’s Rare Earth Dominance

Part I - Rare Earths: The Invisible Backbone, Sept. 4

The Problem — What’s broken, and why it matters

Part II - Rare Earths: The Middle Kingdom’s Monopoly, Sept. 11

The Context — How we got here, and what’s been tried

Part III - Rare Earths: The Race to Rebuild, Sept. 18

The Solutions — What’s possible, and who’s leading the way

The Control Problem: Solving For AI Safety

Part I - AI: The Race and the Reckoning, Oct. 2

The Problem — What’s broken, and why it matters

Part II - AI: The Prisoner’s Dilemma, Oct. 9

The Context — How we got here, and what’s been tried

Part III - AI: The New Nuclear Moment, Oct. 16

The Solutions — What’s possible, and who’s leading the way

The Democracy Deficit: Solving for Competition in the People’s House

Part I - Congress: The Vanishing Competition, Oct. 31

The Problem — What’s broken, and why it matters

Part II - Congress: How We Got Stuck, Today

The Context — How we got here, and what’s been tried

Part III - Congress: The Competitive Cure, Upcoming

The Solutions — What’s possible, and who’s leading the way