War & Peace, Pt 2: From 1989's Hope to Rearmament

Part 2 of 3: The Forces — How the optimism unleashed by the end of the Cold War unraveled — and why the world is arming again.

In Part Two of our series examining the massive military buildup underway around the world—the biggest rearmament since the Cold War—we explore the forces that brought us here. If you missed it, check out part one unpacking the problem. Next week, we’ll explore solutions.

What you’ll learn in part two:

Why the post-Cold War belief that democracy, free markets, and rule of law would spread globally failed to materialize.

How five compounding forces transformed 1989’s optimism into today’s rearmament. They are: uneven benefits of globalization, China’s rise without democracy, Russia’s rejection of the post-Cold War order, social media weaponizing grievance at scale, and American withdrawal from global leadership.

Solving For tackles one pressing problem at a time: what’s broken, what’s driving it, and what can be done. New posts weekly. Previous series examined rare earth elements, AI safety, vanishing competition in Congress, and the end of amateurism in college sports.

At around 11:20 p.m., Harald Jäger picked up the phone again, demanding guidance from his superiors.

“We have to do something!”

It was November 9, 1989.

His superiors had nothing. No orders. No guidance. Only the same confusion Jäger could hear through his office window at the Berlin Wall checkpoint at Bornholmer Straße—the border crossing between East and West Berlin he had guarded for twenty-five years.

Outside, thousands of East Germans were demanding to be let through.

“Open the gate!” they chanted.

Jäger had already tried what his superiors suggested: letting the loudest agitators cross and stamping their passports so they could never return.

The crowd grew larger, louder, more insistent.

Jäger was forty-six years old. A lieutenant colonel in the Stasi, East Germany’s state security service. He had volunteered for the border police at eighteen and spent his adult life following orders. For twenty-eight years, the Wall had divided Berlin—the Cold War’s most visible symbol. The rules were clear: no one crossed without authorization.

Four hours earlier, Jäger had been eating a sandwich in the guards’ canteen, watching the evening news.

Then Günter Schabowski appeared on the screen.

The East German Politburo spokesman looked uncertain, fumbling through his notes as he announced new travel regulations. East Germans, he said, would soon be permitted to cross into the West.

A reporter asked when.

Schabowski hesitated.

“To my knowledge, this takes effect immediately,” he said — a declaration later acknowledged as a mistake.

Jäger nearly choked.

“Bullshit!” he shouted at the television.

He rushed to his office and called his superior.

“You’re calling me because of this nonsense?” his boss snapped.

Send them home. No crossing. Nothing has changed.

Outside, the crowd kept growing. By 9 p.m., thousands filled the street. Over the next two hours, Jäger called his superiors repeatedly. Each time: send them home, no crossing.

At 11 p.m., Jäger understood something his superiors—safely removed from the scene—did not. This was no longer a crowd that could be controlled. It was pressure that could only be released.

“That’s when I said to myself,” he would later recall, “‘Now it’s for you to act.’”

A little before 11:30 p.m., Jäger called his commanding officer once more, who again insisted no one be let through. But this time, for the first time, Jäger would not follow orders. Instead, he gave the order that triggered the collapse of East Germany.

“Open the barrier.”

The red-and-white arm lifted. East Germans surged forward—first dozens, then thousands, eventually tens of thousands—flooding into West Berlin.

It was peaceful. Jubilant. Some kissed the stunned guards as they passed. Others laughed. Others cried. Faces lit by moonlight and disbelief—people seeing the other side for the first time.

Jäger stood still and watched his world collapse.

Later that night, he found a stairwell and wept.

“I didn’t open the Wall,” Jäger later said. “The people who stood there—they did it. Their will was so great, there was no other alternative but to open the border.”

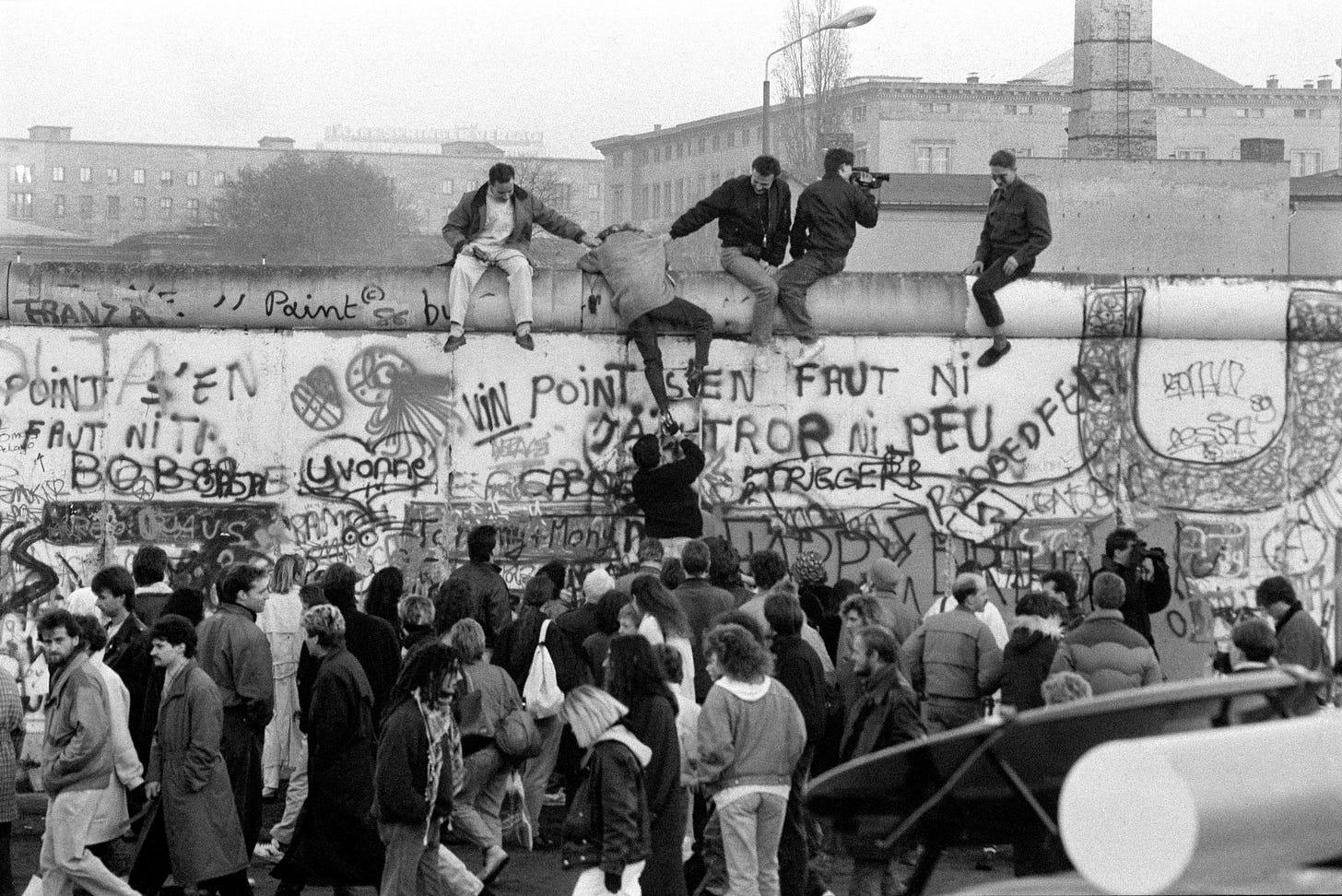

Across Berlin, people climbed the Wall with sledgehammers and champagne. Concrete cracked. Music played. Strangers embraced. East and West blurred together in the cool night air.

The celebration felt universal. Not just German. Not just European. It felt as if history itself had turned a corner.

Within months, communist governments across Eastern Europe collapsed. Within two years, the Soviet Union itself was gone. A world defined by ideological confrontation dissolved with astonishing speed.

In that moment, political scientist Francis Fukuyama gave voice to a belief widely shared in the West: liberal democracy and free-market capitalism had not merely won—they had won permanently. History, as a contest between rival systems, had reached its endpoint.

“The end of history,” he called it.

The evidence appeared unmistakable.

The Soviet Union had collapsed without a great-power war. An empire armed with thousands of nuclear weapons dissolved through negotiation, exhaustion, and internal decay. Democratic systems spread across Eastern Europe, much of Latin America, and parts of Asia. Market capitalism became the global norm. Even China—while retaining one-party rule—embraced economic reform and integrated itself into the global trading system.

The logic seemed airtight: Economic integration would lead inevitably to political liberalization. Prosperity through trade would make war irrational, even obsolete.

For a time, reality appeared to cooperate.

Defense budgets fell. Borders opened. Supply chains stretched across continents. Former adversaries became trading partners. The “peace dividend” was lived, not theorized—visible in rising living standards and a generation that came of age without fear of global war.

Yet more than three decades later, that confidence looks dangerously naive.

The international system built after World War II—designed to replace raw power with rules, institutions, and restraint—is fracturing. Democracy is retreating. The United States is pulling back from the institutions it built.

And amid growing distrust, the world is rearming at a pace not seen since the Cold War. Last year marked the steepest increase in global military spending since the Berlin Wall fell. More than 100 countries increased military spending last year, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Which raises the question: What happened?

How did that jubilant November night in Berlin give way to a world once again defined by great-power rivalry?

The answer lies not in a single cause, but five compounding forces that emerged between 1989 and today—each amplifying the others, each eroding the foundations of the order that followed the Wall’s fall.

Globalization Without Shared Prosperity

Globalization was supposed to lift all boats. In the 1990s, it did. Trade expanded. Supply chains stretched across continents. GDP grew. Poverty fell in developing nations.

But the gains landed unevenly.

In the United States and much of Europe, factory towns hollowed out. Jobs moved overseas. Wages stagnated. One example: from 2000 to 2013 middle-class incomes in the U.S. actually dropped 5 percent, according to the Center for American Progress.

The political class defended the outcomes. Economists pointed to aggregate gains. The U.S. had grown from a roughly $6 trillion economy in 1990 to $29 trillion in 2024, making it by far the largest economy in the world (China is second at $19 trillion).

But for millions of people, it didn’t feel like progress—it felt like abandonment.

Trust in institutions eroded quietly at first, then all at once. In 2016 voters in the U.K. passed Brexit, leaving the European Union. Later that year U.S. voters elected Donald Trump on an “America First” agenda. Populist movements surged worldwide.

Foreign policy requires domestic legitimacy. When people stop believing the system works for them, they stop supporting the global order that system built. The consent that sustained decades of international engagement began to crack—and with it, the willingness to defend the rules that kept the peace.

China’s Rise — When Growth Didn’t Mean Democracy

Through the 1990s and 2000s, the assumption was clear: integrate China into the global economy, and political liberalization would follow. Markets would create a middle class. A middle class would demand rights. Authoritarianism would soften, then fade.

It didn’t happen.

China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, accelerating its integration into the global economy. China grew—massively. It became the world’s factory, then the world’s second-largest economy. Living standards rose. A middle class emerged. Technology advanced. And the Communist Party remained firmly in control.

The “end of history” thesis rested on a simple assumption: economic development and democracy went hand in hand. China disproved it.

The implications were strategic, not just ideological. China’s industrial scale reshaped global supply chains. Its state-directed economy blurred the line between market competition and national strategy. Economic interdependence—once seen as a source of stability—became a tool of leverage and coercion, such as its dominance in mining and manufacturing rare earth elements.

That reality hardened when Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, ending the illusion that economic integration would make China more politically open or democratic, and embracing a nationalist vision of centralized, state-led power.

The system had been designed to integrate rising powers. It was not built to manage what happened when integration produced a powerful rival operating by different rules.

Russia’s Rejection

Russia tried integration. In the early 1990s, Moscow opened its economy, adopted market reforms, and sought partnership with the West. The results were catastrophic.

GDP fell by some 40 percent. Life expectancy plummeted. Oligarchs looted the country’s assets while ordinary Russians watched their savings evaporate. Humiliation became the defining experience of a generation.

By 2000, Vladimir Putin came to power with a simple mandate: restore order. He rebuilt the state around security services and oil and gas money. And he drew a lesson from the chaos: integration was a threat, not an opportunity.

External confrontation became a source of internal legitimacy. In a 2007 speech at the Munich Security Conference, Putin publicly declared an end to Russia’s post–Cold War accommodation with the West. Starting with Georgia in 2008, Putin reintroduced force as a tool of statecraft — seizing Crimea in 2014, intervening in Syria in 2015, and invading Ukraine in 2022.

Russia tested whether the rules still held. Could borders be redrawn by force? Could sovereignty be violated without consequence? Could the international system push back—or was it too fractured, too distracted, too uncertain to respond?

The answer, increasingly, was the latter. When aggression goes unanswered, other states take notice. Rearmament spreads not because of ideology, but because the alternative—trusting restraint—begins to look dangerously naive.

Social Media and the Fracturing of Trust

By the 2010s, social media didn’t just reflect economic grievance or political division—it scaled them.

The timing mattered. As globalization accelerated in the 2000s, a new digital layer emerged alongside it: Facebook launched in 2004, Twitter in 2006—platforms that would soon shape how billions of people consumed information and understood politics.

Social media platforms, optimized for engagement, discovered that outrage drives clicks. Algorithms amplified anger, identity conflict, and grievance. What once burned slowly—resentment over job loss, frustration with elites, anxiety about cultural change—now spread at scale, at speed.

Shared facts eroded. Different communities consumed entirely different information ecosystems. Consensus became nearly impossible to build, even on basic realities. Democracies, which depend on some baseline agreement about truth, found themselves fracturing from within.

The effects weren't only domestic. Social media became a tool for state and non-state actors to sow discord.

Russia demonstrated this most dramatically in 2016, using Facebook to amplify existing American grievances—many rooted in globalization—in support of Trump's explicitly anti-globalist, anti-establishment candidacy, according to the bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee Report.

It was a case of multiple forces converging: Russia's rejection of Western integration, social media's capacity to scale division, and social fractures created by globalization itself.

Politics requires cooperation, cooperation requires trust, and trust requires shared reality. As that reality fractured, states began planning for worst cases. If you can’t trust your information environment, you can’t trust your adversary’s intentions. And if you can’t trust intentions, you prepare for conflict.

Social media made democracies harder to govern and the international system harder to sustain—even without a single shot fired.

American Withdrawal

The United States built the post-World War II system. It wrote the rules. It funded the institutions—the United Nations, NATO, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund. It provided security guarantees that allowed former adversaries to become allies: protecting Japan and Germany, stationing troops across Europe and Asia, underwriting the defense of dozens of nations. For decades, American leadership—however imperfect—held the system together.

The system replaced spheres of influence—where great powers dominated their regions through force—with a framework where nations pursued their interests through rules, institutions, and negotiation rather than military strength alone. It created the longest peace between global powers since the Roman Empire.

Then it stopped.

The shift began gradually. After the Cold War, American commitment became inconsistent. George W. Bush pulled back from multilateralism, rejecting the Kyoto Protocol and launching the Iraq War unilaterally. Barack Obama leaned back in, championing the Iran nuclear deal and Paris climate agreement. Then Trump rejected both. Diplomacy was underfunded relative to defense. Alliances were treated more transactionally. Multilateral institutions were seen as constraints rather than tools.

By the 2010s, inconsistency had become ambivalence. The United States remained militarily dominant but politically uncertain about whether it still wanted to lead.

Now, that ambivalence has turned to explicit rejection.

In November the Trump Administration published its 2025 National Security Strategy declaring that “the days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.” The administration argues that post-Cold War elites “lashed American policy to a network of international institutions, some of which are driven by outright anti-Americanism and many by a transnationalism that explicitly seeks to dissolve individual state sovereignty.”

Trump himself derides alliances like NATO as protection rackets. Trade agreements torn up amid a wave of tariffs. International institutions dismissed — the U.S. withdrew from 66 multilateral organizations in January 2026 alone, the White House announced.

The message is clear: the United States will no longer serve as steward of the order it created.

The problem is structural. The system was designed to function by members enforcing the rules. Remove the enforcer, and the rules become suggestions. Other states—some hostile, some merely opportunistic—fill the void. What remains is competition without guardrails.

When Forces Compound

These five forces didn’t operate in isolation. They compounded.

Each force made the others more dangerous. Economic anxiety fed nationalist politics. Nationalist politics rejected multilateral cooperation. The absence of cooperation emboldened countries, like Russia, willing to challenge the rules. Challenges without consequences convinced other states that restraint was a liability. And technology, particularly social media, accelerated every stage of the breakdown.

What followed is not chaos—it’s rearmament. States are looking at a world with weakened institutions, eroding norms, and rising tensions, and concluding they need to prepare for conflict. Not because war was inevitable, but because the mechanisms that made restraint rational had broken down.

That November night in Berlin in 1989 carried such hope. As the Wall fell, it felt to many like history itself had turned a corner. Political scientist Fukuyama gave voice to that moment, arguing that liberal democracy and free markets had proven themselves the most durable form of human governance—famously calling this “The End of History.”

Perhaps that judgment was premature rather than wrong. But the mechanisms that maintained the 80-year peace between great powers are breaking down. Whether they can be rebuilt—and what that rebuilding requires—will define not just the coming decade, but the rest of this century.

Next week: Solutions.

Note: Prefer to listen? Use the Article Voiceover at the top of the page, or find all narrated editions in the Listen tab at solvingfor.io.