College Sports: How It Was Broken By a $60 Video Game

Part 1 of 3: The Problem — Ed O'Bannon's discovery triggered a legal revolution that shattered the facade that had masked college sports' central contradiction. But what comes next?

For this series we focus on college sports undergoing its most dramatic transformation in a century. One of America’s most beloved institutions—built into a multi-billion-dollar enterprise on unpaid athletes—has finally cracked. What comes next remains profoundly uncertain.

The challenge: compensating athletes who generate billions while preserving the traditions and educational purpose that gave it meaning—and sustaining the non-revenue Olympic sports that football and basketball have historically funded.

Today’s installment examines the problem; next week, the forces that brought us here; the third part, solutions.

What you’ll learn in part one:

How Ed O’Bannon’s discovery exposed amateurism’s contradictions and triggered the legal chain reaction now reshaping college sports.

Why the NCAA’s historic settlement dismantled the old model without building a coherent replacement — leaving critical questions unresolved.

What those unresolved questions mean for the future of college athletics, from employee status to Title IX to the survival of non-revenue sports.

Solving For tackles one pressing problem at a time: what’s broken, what’s driving it, and what can be done. New posts weekly. Check out previous series on rare earth elements, AI safety and vanishing competition in Congress.

On a hot, lazy Saturday afternoon in April 2009 in the Las Vegas suburb of Summerlin, former UCLA All-American Ed O’Bannon saw something that would change college sports forever.

Standing in his friend Mike Curtis’ living room, he watched Curtis’ nine-year-old son play an EA Sports basketball video game on an Xbox 360. On the screen was number 31 for UCLA. Six feet, eight inches. Two hundred twenty-two pounds. Power forward. Left-handed.

O’Bannon saw his number. His height and weight. His position. Even his shooting motion. The only thing missing was the name on the back. In every meaningful way, with uncanny accuracy, he was looking at himself.

Fourteen years had passed since O’Bannon led UCLA to its 11th national championship and was named the tournament’s most outstanding player. His pro career had never turned into stardom, but he’d saved money from his time in the NBA and seasons in Europe. Now he was selling cars at Findlay Toyota in Henderson, Nevada, raising three kids with his wife, Rosa.

At first, he was flattered—thrilled, even—to see himself and his 1995 teammates rendered so vividly in EA Sports’ NCAA March Madness.

Then Curtis, half-joking, said: “Dude, can you believe I paid sixty bucks for this thing?”

O’Bannon’s smile vanished. He looked away from the TV and out a window. The moment didn’t sit right. He had never given permission for his likeness to be used. He hadn’t been paid a penny. He felt powerless.

“I went back to work the next morning and put it out of my mind,” O’Bannon recalled in his book, Court Justice.

A few weeks later, sitting at his desk at the dealership reviewing a list of incoming cars, a longtime mentor called. The mentor was preparing a class-action lawsuit against the NCAA for profiting off former players’ names, images, and likenesses. He wanted O’Bannon to be the lead plaintiff.

O’Bannon said yes. What followed would expose a contradiction that had been building for decades.

The case—O’Bannon v. NCAA—would collide head-on with the NCAA’s most sacred principle: that, in the name of amateurism, college sports could generate billions of dollars for conferences, coaches, administrators, broadcasters, video game makers, and apparel companies—but not for the athletes who made it possible.

It became the moment the façade cracked.

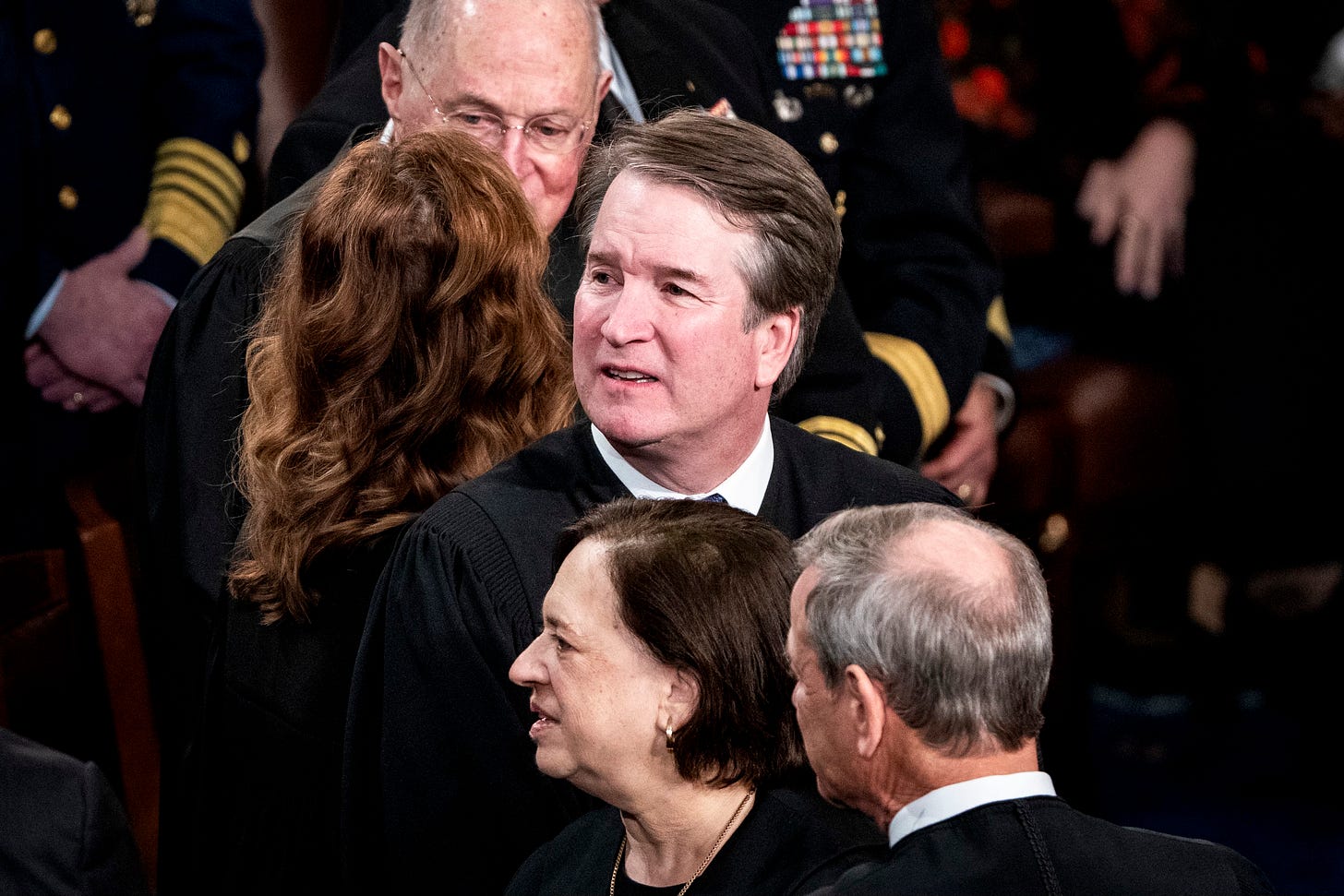

O’Bannon’s case didn’t dismantle the NCAA’s model, but it opened the door. Over the next decade, more antitrust lawsuits chipped away at amateurism, culminating in a 2021 Supreme Court ruling in NCAA v. Alston that struck down the NCAA’s limits on education-related benefits. Justice Brett Kavanaugh went further, noting in a concurring opinion that unpaid college athletes generate billions of dollars in revenue for colleges, yet “enormous sums of money flow to seemingly everyone except the student-athletes.”

He concluded: “The NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America.”

Then, this summer, came a watershed moment: the House settlement, named for Arizona State swimmer Grant House who filed the suit in 2020 alongside other athletes. Facing a tidal wave of litigation and billions in potential damages, the NCAA decided to stop fighting and agreed to a sweeping settlement in consolidated class-action lawsuits.

The settlement requires $2.8 billion in back damages paid over ten years to athletes denied name, image and likeness opportunites — otherwise known as NIL — since 2016.

Most significantly, schools can now directly pay athletes for the first time in NCAA history — up to roughly $20 million per year per school, derived from 22 percent of athletic department revenue from media rights, ticket sales, and sponsorships. Scholarship limits are abolished and replaced with roster caps — preventing roster inflation while dramatically expanding scholarship opportunities. A newly-created College Sports Commission enforces the revenue-sharing cap and regulates NIL deals.

It was billed as the dawn of a new era.

But the House settlement dismantled amateurism without delivering a coherent model to replace it. College sports has now entered an era where the old rules have collapsed and the new ones are not yet written.

At its core, college sports faces an impossible contradiction: how to compensate athletes who generate billions while preserving the traditions and educational purpose that gave the enterprise meaning—and sustaining the non-revenue sports that football and basketball have historically funded.

The problem isn’t just that the old model is gone; it’s that no one agrees on what should replace it.

The Wild West

College sports occupies a place in American culture unlike almost anything else.

Autumn football Saturdays in Ann Arbor and Tuscaloosa. Raucous basketball arenas in Chapel Hill and Lexington. March Madness office pools and buzzer-beaters. The College Baseball World Series in Omaha and Softball World Series in Oklahoma City. Future Olympians competing for track and field national championships in Eugene. Generations of families who never attended a university but bleed its colors anyway. It’s not just entertainment—it’s identity, ritual, belonging.

That’s what makes the current crisis so fraught. What’s collapsing isn’t just a business model. It’s a century-old institution that millions of people feel they own, built on ideals that—however imperfectly realized—gave it meaning beyond money.

College sports now exists in no man’s land—the old model dead, the new one unwritten. The NCAA’s repeated failures to adapt intelligently made things worse at every turn.

Case in point: on June 30, 2021, only nine days after Kavanaugh’s scathing Supreme Court opinion, and with state laws threatening its authority, the NCAA suspended its own rules limiting players being paid for their name, image, or likeness—otherwise known as NIL. Overnight, college athletes could sign endorsement deals with no clear guidelines about what was permitted. The NCAA promised regulation would follow. It never meaningfully did.

Instead, more than 30 states passed their own NIL laws, each with different rules. Some prohibited the NCAA from enforcing any restrictions. Others set their own limits. Booster-funded collectives formed at nearly every major program, offering recruits six- and seven-figure deals that functioned as signing bonuses in everything but name.

Basketball phenoms like Duke’s Cooper Flagg signed deals with New Balance and Fanatics reportedly totaling $28 million — as a college freshman. This week the University of Miami landed Jackson Cantwell, the most highly touted high school offensive lineman in the country, on a scholarship offer that reportedly includes an NIL deal worth some $2 million a year. There was no oversight, no enforcement, and little transparency about who was paying whom or why.

Meanwhile, spending on coaches skyrocketed. Last weekend Lane Kiffin accepted the head football coaching job at Louisiana State University with a contract paying him $91 million over the next seven years — and that doesn’t make him the highest paid coach in college football. The University of Georgia is paying Kirby Smart $130 million over ten years to coach its football team.

A Congressional Research Service report captured the moment: “college athletics has entered a period some commentators and Members of Congress have referred to as the ‘wild west.’”

NCAA President Charlie Baker — the former Massachusetts governor hired by the NCAA in March 2023 to figure out a way forward — was blunt about the damage: “The result was a sense of chaos: instability for schools, confusion for student-athletes and too often litigation.”

The House settlement was supposed to bring order. Baker called it “a pathway to begin stabilizing college sports,” finally addressing the core injustice that Ed O’Bannon exposed in 2009 and that Justice Kavanaugh condemned in 2021.

With revenue sharing, scholarships, and other benefits combined, Baker said that student-athletes at many schools will now receive nearly 50 percent of all athletic department revenue. He called it “a tremendously positive change and one that was long overdue.”

But by Baker’s own admission, the settlement left fundamental issues unresolved. College sports now sits between what no longer works and what hasn't yet been designed — and the system’s biggest questions lie squarely ahead.

The Unresolved Questions

Are Athletes Employees?

The settlement’s most glaring omission: it deliberately sidestepped the question at the heart of modern college athletics: whether athletes are students who play sports or workers who attend school.

Courts and labor boards are already pushing toward an answer. Last year, after Dartmouth basketball players sought to unionize, the National Labor Relations Board ruled they are employees who can form a union—even though they receive no scholarships and play in a league that generates minimal revenue. The team dropped its unionization effort earlier this year, but the precedent was set.

If athletes are employees, they become entitled to minimum wage, overtime, workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance, and the right to unionize. Few universities are prepared for what that shift would mean. Revenue-generating sports like football and basketball might absorb the added costs, but non-revenue Olympic sports—swimming, wrestling, track, tennis—would face immediate jeopardy.

Most athletic departments cannot afford to treat hundreds of athletes as employees while maintaining their current roster of sports. The potential result: schools will cut programs or, perhaps, leave Division I altogether.

Can the Salary Cup Survive Legal Challenge?

Professional leagues have salary caps because they have unions and antitrust exemptions. College athletics has neither.

Yet the House settlement includes a $20.5 million cap on what schools can pay athletes—without the legal protections that make salary caps work in the pros. For instance, there is no collective bargaining agreement with a players’ union, and no antitrust exemption from Congress.

That contradiction raises legal questions. The Department of Justice warned in a January 2025 filing in the House case that the cap “restrains competition among schools” and allows the NCAA to continue fixing compensation. An ongoing question is whether the cap can withstand antitrust challenges that could invalidate the settlement’s core framework.

The Title IX Collision

Unlike NIL deals with third-parties like college boosters or sneaker companies, direct payments from schools must comply with federal gender-equity law. But football and men’s basketball generate the overwhelming majority of revenue while Title IX — signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1972 — requires equal educational opportunity, including athletics, between men and women.

Texas Tech, for instance, plans to allocate more than 90 percent of its revenue-sharing funds to men’s sports, according to one report. How Title IX applies to direct payments is an unresolved legal question, but lawsuits are almost certain and universities may be forced to pay athletes in ways that conflict with the economics of their own departments.

The Threat to Olympic Sports

Revenue sharing doesn’t bring new money into college athletics — it diverts existing money out of athletic department budgets and into direct payments to players. Meanwhile, NIL collectives — college boosters who pool their money together — can also have the effect of pulling donor support away from an athletic department generally and towards specific sports and players.

The result is a shrinking pool of funds for everything beyond football and men’s basketball.

Because most non-revenue sports cost millions to run and generate little in return, they become the pressure point. Estimates suggest thousands of athletes across swimming, wrestling, gymnastics, track, volleyball, rowing, and other Olympic sports could lose opportunities as schools confront the new financial reality.

The fear is real—that an era intended to make college sports fairer may end up shrinking the universe of athletes who get to compete at all, including many who form the backbone of America’s Olympic pipeline.

Who’s in Charge?

The newly formed College Sports Commission—created as a result of the House settlement—now oversees revenue sharing and NIL deals for all Division I schools. The organization requires all NIL contracts over $600 to be reported and approved to ensure they reflect “fair market value” rather than disguised pay-for-play.

But the Commission is untested, launching just months ago with no track record. And it is still sorting out its authority—last month, for instance, it sent letters to schools under its purview asking them waive their right to challenge future punishments in court. Adding to the complication, states have passed conflicting NIL laws. Meanwhile, the NCAA still handles other rules—academic eligibility, rules of competition, sports betting.

In sum, college sports now operate under a fragmented regulatory structure unprecedented in its modern history.

What is College Sports Supposed to Be?

This is the question behind all the others. Student athletes are now being compensated like professionals, trained like professionals, and scheduled like professionals—while still expected to maintain the full academic load of traditional students. The educational mission that once justified the enterprise no longer matches its economic reality.

If this is now openly commercial, what distinguishes it from a minor league? If it remains tied to universities, how do schools reconcile academic values with entertainment revenue? The answer will determine whether college sports survives as a distinct institution—or collapses into something unrecognizable.

Not The First Crisis

Ed O’Bannon’s discomfort at finding his own likeness in a video game he’d never authorized — and for which he’d never been paid — set off a chain reaction. One lawsuit triggering another, one ruling forcing the next, each cracking the façade a little more. By the time the House settlement arrived, amateurism wasn’t reformed — it was finished.

Yet, this isn’t the first time America’s colleges and universities grappled with an existential crisis over athletics. A century ago, when football became so dangerous that players were dying, some called for the game to be banned.

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in. He convened two White House summits on college football in October 1905, using the bully pulpit to force college leaders to reform a sport on the brink of being outlawed. Those meetings set in motion the creation of what would become the NCAA.

More than a century later, the current crisis will likely require Washington to step in again.

The question is: how?

Next up: How we got here — and, then, the solutions leaders are proposing to get out of it.

Note: Prefer to listen? Use the Article Voiceover at the top of the page, or find all narrated editions in the Listen tab at solvingfor.io.