College Sports: How the NCAA was Born of Death and Money — Death was the Easy Part

Part 2 of 3: The Forces — How the Money Problem Finally Won.

In Part Two of our series, “The Amateur Myth: Solving For College Athlete Pay,” we trace the forces that brought college sports to this moment of reckoning — how a model built on “amateurism” fractured under the weight of money, power, and contradiction, and how a scramble to construct something new is now underway.

If you missed Part One, see it here. In Part Three, we'll examine solutions. For this installment — how we got here — we’ll learn:

How the NCAA’s founding promise to separate college sports from money was compromised almost from the start.

How “amateurism” evolved into a legal fiction that protected institutions, even as a billion-dollar industry grew around unpaid athletes.

Why that fiction finally collapsed — and why college sports now face their most consequential test in more than a century.

In October 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt summoned college football’s leaders to the White House. The sport had exploded in popularity — so much so that Princeton’s president, Woodrow Wilson, quipped that the university “is noted in this wide world for three things,” and the first was football.

But the game had two problems: death and money.

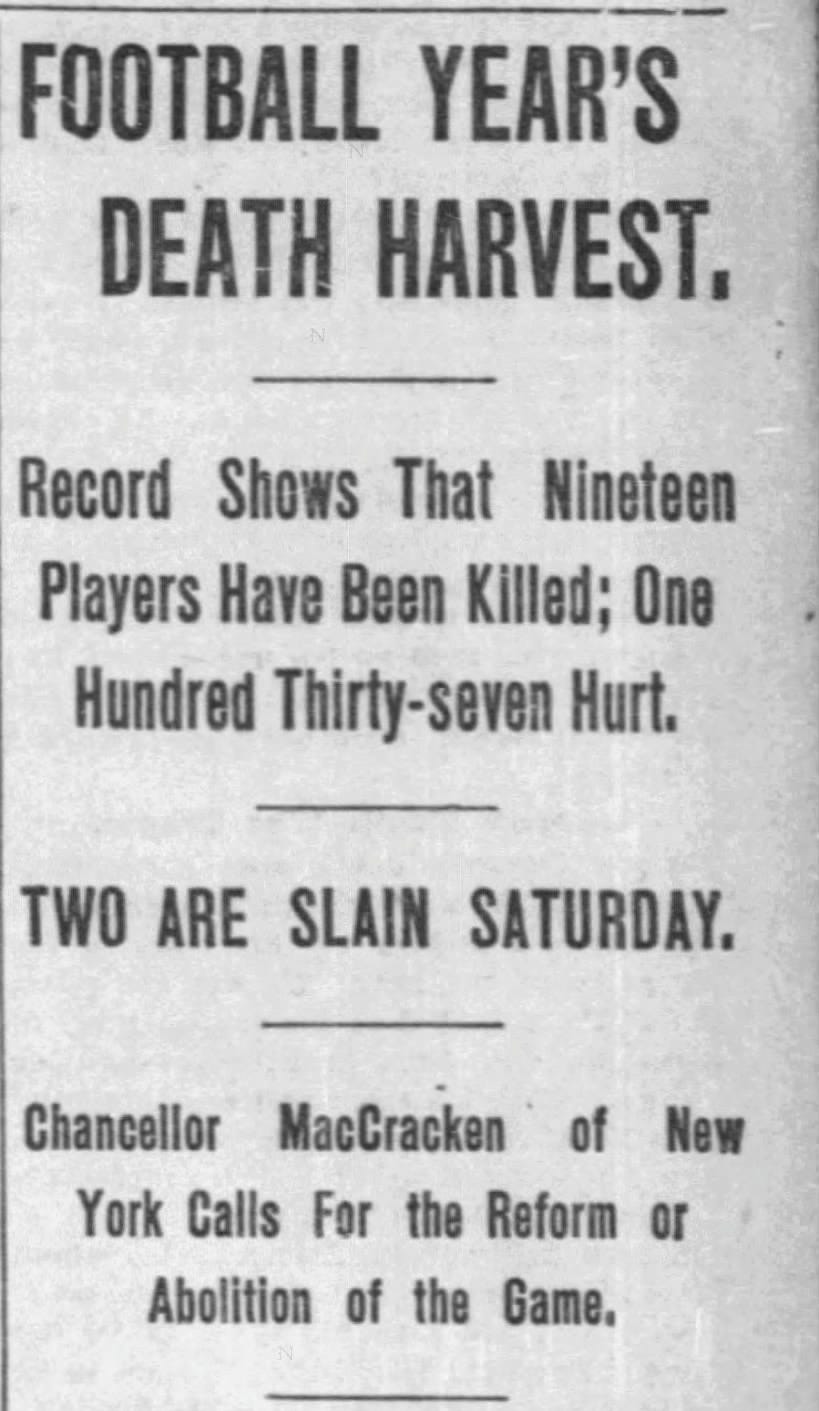

That year, 19 players died playing football. The Chicago Tribune called it football’s “Death Harvest.” Obituaries of dead players appeared almost weekly during the season. Columbia shut down its football program. Stanford and Cal-Berkeley switched to rugby. Roosevelt issued a blunt ultimatum: reform the sport or he would ban it outright.

Corruption was the other crisis. Colleges were paying ringers. Princeton, Harvard, and Yale were accused of hiring “tramp athletes” — itinerant players who roamed the country playing for whoever paid best. One leading reformer warned that “our supposedly amateur college athletics” was plagued by “various forms of payment… for their athletic services.”

Out of those meetings emerged in 1906 the organization that would become the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Its mandate: make the game safer and clean up its corruption.

The first goal produced some of the most consequential rule changes in football history: legalizing the forward pass, abolishing mass-momentum formations like the flying wedge, and penalizing unsportsmanlike play.

The second goal drew a hard line. The new association took an uncompromising position on amateurism: no payment or compensation allowed of any kind. The NCAA’s founding constitution was explicit: No student shall represent a college or university in any intercollegiate game “who is paid or receives, directly or indirectly, any money.”

Football’s fatal violence was eventually tamed.

Money never was.

Instead, America’s colleges and universities tightened — rather than untangled — their relationship with sports and money. While insisting athletes remain amateurs, over the next 119 years they built a professionalized, billion-dollar ecosystem around them. That contradiction — ignored, patched over, defended for so long — has finally blown open.

Now, the NCAA faces a reckoning unlike anything since dead players were being carried off the field in the early 1900s. The question is no longer whether the old model can survive, but what comes next: How do you compensate athletes who generate billions while preserving educational purpose, beloved traditions, and the non-revenue Olympic sports that football and basketball have long subsidized?

The End of Amateurism

The NCAA formally raised the white flag this summer, ending the amateur ideal it had trumpeted at its founding and vigorously defended for more than a century in courtrooms and editorial pages.

By settling a series of antitrust lawsuits in June, collectively known as the House settlement, the NCAA declared that schools can now directly pay student-athletes under a revenue-sharing plan in which each school may distribute roughly $20 million annually to its players.

NCAA President Charlie Baker called it a “new beginning.” But the settlement left many questions unresolved. Are athletes now employees? What happens to non-revenue sports as a significant share of athletic department budgets shift to player pay? What, fundamentally, is college sports supposed to be now?

The result is an awkward limbo: the old model collapsed, little agreement on what should replace it, and professionalization accelerating faster than governance can keep up.

In the past ten days alone, the turbulence has been unmistakable.

First, Congress declined to advance NCAA-backed federal legislation that would have resolved some of the open questions — including antitrust protection and explicitly barring athletes from employee status. “Not ready for prime time,” Rep. Chip Roy, a Texas Republican, posted about the legislation on X, adding: “don’t just professionalize this stuff and pretend you aren’t doing exactly that.”

Then, days later, professionalization surged forward. The University of Utah became the first school to take private-equity money, announcing a joint venture with Otro Capital that could generate more than $500 million for its athletic program.

As recently as October, NCAA President Baker warned schools to “be really careful” with private equity. Among the risks is that private equity prioritizes financial returns above all else, fully sidelining educational mission and turning college teams into de facto professional franchises. That dam has now cracked.

Always a Fiction

From the NCAA’s founding in 1906, there was little evidence that colleges truly intended to embrace amateur athletics.

A few institutions — such as the University of Chicago, Harvard, and Yale, which were athletic powerhouses at the time — would later pull back from big-time college sports. But across the country, the gravitational pull was in the opposite direction.

By the 1920s, accusations of paid players and booster interference filled newspapers. In response the Carnegie Foundation launched a sweeping investigation.

Its 1929 report was devastating. Universities, it found, were running professional sports programs in everything but name. College football, the report concluded, has turned into “professionalized athletic contests for the glory and, too often, for the financial profit of the college.”

This was nearly a century ago.

Yet the fans kept coming. And most universities didn’t reform — neither pulling back from big-time sports nor acknowledging that college athletics had become a commercial enterprise dependent on athletes’ labor.

Instead, they doubled down on a version of amateurism that applied only to the players, even as institutions accumulated ever-larger fortunes from packed stadiums — and, later, television contracts.

Behind the moral posturing, the under-the-table payments never stopped — they were simply denied. In the 1940s, Hugh McElhenny, a University of Washington running back, became known as the first college player “ever to take a cut in salary to play professional football.”

Publicly, universities preached amateurism and threatened punishment. Privately, they paid what it took to win — and punished only those who got caught.

Yet, by the 1950s, the NCAA’s ideals outpaced its power, lacking the structure to enforce its brand of amateurism.

Then came Walter Byers.

The Invention of the “Student-Athlete”

When Walter Byers became the NCAA’s executive director in 1951, it was a small nonprofit with four staff members. By the time he left in 1987, it presided over a multibillion-dollar industry. Byers didn’t just grow the organization—he designed the modern architecture of college sports.

Following his 2015 death, Byers was called “one of the 20th century’s most powerful sports figures” in a New York Times obituary.

He consolidated control through college sports television revenues and built the men’s basketball championship — March Madness and the Final Four — into a financial juggernaut. He constructed an enforcement apparatus with real penalties, including postseason bans. Money, governance, and enforcement gave the NCAA real teeth — and Byers enormous power.

Yet, Byers’ most consequential invention was a two-word name. In September 1955, Fort Lewis A&M football player Ray Dennison died after a collision on the field. His widow, Billie, sought workers’ compensation death benefits.

Byers understood the threat.

His solution: he created the term “student-athlete.”

It was inserted into NCAA manuals, university communications, media guides. These weren’t athletes who happened to be students; they were students who happened to play sports. Students don’t get workers’ comp. Students aren’t employees.

The Colorado Supreme Court agreed — ruling against Dennison’s widow. Football players were “student-athletes,” not employees. Workers’ comp didn’t apply.

As Pulitzer-prize winning historian Taylor Branch would write in a 2011 essay in The Atlantic calling for college athletes to be paid, the term was cynically created not to protect education, but to shield universities from liability.

“Amateurism” and “student-athlete” are, Branch wrote, “legalistic confections propagated by the universities so they can exploit the skills and fame of young athletes.”

Big Money, Then Everything Else

Television transformed college sports slowly — then all at once.

The NCAA’s first TV deal inked by Byers in 1952 was modest. But it grew and grew. So much so that, by the early 1980s, the University of Oklahoma and the University of Georgia sued the NCAA, arguing they should be allowed to negotiate their own television deals. In 1984, the Supreme Court — in a case called NCAA v. Board of Regents — struck down the NCAA’s television monopoly on antitrust grounds. The decision was meant to limit NCAA power. Instead, it unleashed a gold rush.

Conferences negotiated their own TV deals. Notre Dame cut its own national TV contract in 1990, now reportedly worth $50 million annually. Cable networks like ESPN, hungry for content, threw money at football and basketball. By the 1990s, TV contracts were measured in millions. By the 2000s, billions. CBS and Turner Sports now pay $1.1 billion a year to televise the Men’s college basketball tournament.

Meanwhile, the NCAA struck licensing deals for everything from apparel to, fatefully, video games.

The result: coaches’ salaries exploded, facilities turned palatial, conference commissioners and NCAA executives were handed ever-richer pay packages. Between 1986 and 2010, major college football coaches saw their salaries increase by 750 percent, according to the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. LSU’s Lane Kiffin and Georgia’s Kirby Smart each earn some $13 million annually.

When NCAA President Mark Emmert stepped down in 2023, he was making more than $3 million annually.

The money went everywhere—except to the athletes.

Yet schools sought even more of it. Conferences were restructured, forcing athletes into exhausting cross-country travel and, in some cases, ending longstanding regional rivalries. Oregon and Washington, for instance, joined the Big Ten, now traveling thousands of miles for conference games against the likes of Maryland and Rutgers.

The incentive was money. When the Big Ten released its tax records in May, they showed the now 18-team conference generating nearly $1 billion annually.

And for executives, the rewards were enormous. The Big Ten’s commissioner, Kevin Warren, earned $6.8 million in 2023, according to USA Today.

Yet even as money flooded the system, the NCAA functioned as a cartel — fixing the price of athletic labor at zero.

Americans loved the idea that college sports were different—purer than the professional game. That everyone else was getting rich didn’t spoil the illusion.

Until it did.

The Convergence

Three trends converged through the 2010s and into this decade.

First, money.

Second, the antitrust lawsuits detailed in Part One of our series — including O’Bannon and Alston — finally cracked the NCAA’s model that long appeared unassailable.

Third, public sentiment shifted. More Americans concluded that not paying college athletes was no longer defensible.

For years, free education was viewed as adequate compensation. The NCAA was applauded for policing corruption.

Taylor Branch’s 2011 essay in The Atlantic captured the moral reversal.

“The real scandal is not that students are getting illegally paid,” Branch wrote. Instead, the “tragedy at the heart of college sports is not that some college athletes are getting paid, but that more of them are not.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s stinging concurrence in the 2021 Alston case crystallized the shift. While ruling on the narrow question of education-related benefits, Kavanaugh signaled that the NCAA’s broader business model would not survive serious antitrust scrutiny.

“The bottom line is that the NCAA and its member colleges are suppressing the pay of student athletes who collectively generate billions of dollars in revenues for colleges,” Kavanaugh wrote, in an opinion published in June 2021. “College presidents, athletic directors, coaches, conference commissioners and NCAA executives take in six- and seven-figure salaries. Colleges build lavish new facilities. But the student-athletes who generate the revenues, many of whom are African American and from lower-income backgrounds, end up with little or nothing.”

Nine days later the NCAA lifted limits on players marketing their name, image and likeness—and from that moment on, college sports was never the same. The only question now is what it will become.

The Architect’s Confession

Ironically, the man who built the NCAA into the powerhouse it became was among the first to realize the system was broken and say so publicly — though his warning came too late to matter.

Eight years after stepping down as NCAA president, Byers wrote a 1995 memoir, Unsportsmanlike Conduct, that condemned the enterprise he built.

“The colleges own the athletes’ bodies,” he wrote, calling the system a “neo-plantation mentality.” Byers called for pay, collective bargaining, and federal oversight.

Most damning was his confession: “None of us wanted to accept what was really happening.”

Looking back 120 years ago, Theodore Roosevelt solved college football’s death problem — and saved the game — with rules.

The money problem, it turns out, could not be solved the same way — because it was never really about rules at all, but about values. About who deserves to share in the wealth college sports generates, and about what fairness looks like in an enterprise that long insisted it was not a business — even as it behaved like one from the start.

Next up: We’ll explore solutions — what does a way forward look like?

Note: Prefer to listen? Use the Article Voiceover at the top of the page, or find all narrated editions in the Listen tab at solvingfor.io.

Solving For tackles one pressing problem at a time: what’s broken, what’s driving it, and what can be done. New posts weekly. Check out previous series on rare earth elements, AI safety and vanishing competition in Congress.

If you find this work valuable, please share with friends. If you were forwarded this, you can subscribe at solvingfor.io.